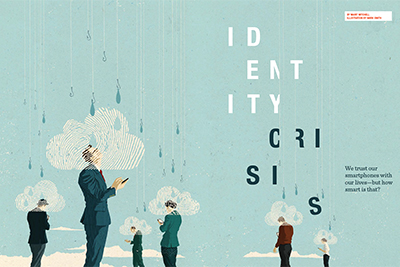

We trust our smartphones with our lives—but how smart is that?

By Marit Mitchell

It wakes up next to you, sits by to you at lunch, hits the gym with you after work. Face it—your smartphone is your best friend. But how good is it at keeping your secrets?

Almost two billion people have a computer in their pockets right now. And we use these smartphones for everything: not just talking and texting, but handling our finances, booking travel, mapping our next run and tracking our medications. We’ve taken our lives in our hands—literally.

All this personal information goes pouring into our devices through the apps we install, and floats magically into some hazily defined realm called ‘the cloud’. But what if a little intel gets stolen along the way? Are we sure our apps aren’t spying on us?

Anecdotal evidence, such as the flap about the Facebook Messenger app collecting audio and video recordings without the user’s permission, indicates our phones may be used against us more often than we realise. “For the average user, the main threat to them is going to be getting fooled into installing some application thinking it’s useful, but it’s doing stuff that they didn’t anticipate,” says Professor David Lie, Canada Research Chair in Secure and Reliable Computer Systems. “A lot of people are worried about this, but no one can answer concretely whether it’s happening.”

Professor Lie’s research group has just launched a project with TELUS to find out for sure. He and his students work on software to improve data security and privacy, both on your device and in the cloud. There’s an important distinction to be made between security and privacy, says Professor Lie. Security is like locking a safe—protecting all information from disclosure absolutely, and making sure that information can’t be accessed without authorization. Privacy is a more complex problem, especially given the ubiquity of smartphones: we want to share everything, but only in specific ways, with specific people, at specific times. “The real problem is that people want to share their information, but have no way of understanding what will happen if they do,” says Professor Lie.

Perhaps the worst data to give away is your biometric information—your fingerprints, retina scans or the unique signature of your heartbeat. Professor Dimitrios Hatzinakos is a leader in the field of medical biometrics and chair of the Identity, Privacy and Security Institute at the University of Toronto, a collaboration between The Edward S. Rogers Sr. Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering and the Faculty of Information. His team searches for new biometrics in the many electrical signals emitted by the human body—unique waves radiating from your brain, bouncing off your eardrum, and given off every time your heart beats.

His former PhD student Foteini Agrafioti teamed up with ECE alumnus Karl Martin to found Bionym, a startup company based on their research on biometrics and security. Bionym recently released the world’s first wearable authentication system, called Nymi, to much acclaim. Nymi is a bracelet embedded with an electrocardiogram (ECG) sensor that recognizes the unique and unchanging electronic signal of your heart and uses it to identify you to all your registered devices to log you in, eliminating the need for passwords and PINs. Bionym has top-notch security, but if your unencrypted ECG were ever compromised, it’s not as easy to fix as resetting your password.

“You have a finite amount of biometric data,” says Professor Stark Draper. “You only have 10 fingers, as opposed to an unlimited number of passwords or credit card numbers.”

That’s why Professor Draper and master’s student Adina Goldberg are trying to find the optimal balance between privacy and security in linked biometric systems. Imagine that your apartment complex, gym and office all use biometric data to authenticate your identity. If all three systems store the same information and an imposter hacks your gym account, they’ll also be able to get into your apartment building and office, but they won’t gain new information about you if they do. That’s bad security, but relatively good privacy. Conversely, if each account stores a unique piece of biometric data, it’s harder to gain access to all three, but each time the imposter hacks a new account they gain more of your sensitive data.

“We’ve seen a trade-off between the two,” says Professor Draper. “Tighter security is of interest to the institution that doesn’t want to get broken into, but the individual might think it’s more important to keep more of their biometrics private and it’s OK if someone breaks into the gym. The system designer gets to pick a point on that curve.”

This tension between the individual and the institution was cast in a new light last year, when whistleblower Edward Snowden alerted the world to the U.S. National Security Agency’s habit of mining personal data directly off servers run by Google, Facebook, Microsoft and others.

“I think for a lot of people in the field, the Snowden leaks came as no surprise,” says Professor Lie. “When I first started doing this cloud stuff, I got a lot of pushback—the logic was, ‘Why would the cloud provider attack their own customers? It doesn’t make business sense.’ Now we can see that they’re not attacking their customers directly, but the data is still vulnerable.” One of Professor Lie’s projects aims to solve the problem of gaining logs from a multi-tenant server—allowing users to see exactly how their information is being accessed, without violating the privacy of all the other users on the same service.

If you don’t have the savvy to interpret server logs but are keen to protect your privacy, taking a critical look at your apps is a good place to start. Professor Lie, for his part, installed a program on his smartphone to prevent applications from talking to the network unless he explicitly gives them permission—not a solution he recommends for everyone. If he does give permission, he reads the privacy policy first. “But sometimes it’s just an exercise in futility,” he admits. “Most of them are pretty impenetrable, or vague about what they do with the information they collect.”

So sleep, eat, jog and bank on your smartphone with caution—with friends like these, who needs enemies?

This feature appeared in the latest issue of ANNUM: read or download the full magazine.

This feature appeared in the latest issue of ANNUM: read or download the full magazine.